Glaucoma is a disease of the optic nerve — the part of the eye that carries the images we see to the brain. The optic nerve is made up of many nerve fibers, like an electric cable containing numerous wires. When damage to the optic nerve fibers occurs, blind spots develop. These blind spots usually go undetected until the optic nerve is significantly damaged. If the entire nerve is destroyed, blindness results.

Early detection and treatment by your ophthalmologist (Eye M.D.) are the keys to preventing optic nerve damage and blindness from glaucoma.

Glaucoma is a leading cause of blindness in the United States, especially for older people. But loss of sight from glaucoma can often be prevented with early treatment.

What causes glaucoma?

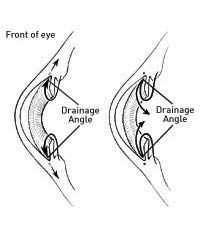

Clear liquid called aqueous humor circulates inside the front portion of the eye. To maintain a healthy level of pressure within the eye, a small amount of this fluid is produced constantly while an equal amount flows out of the eye through a microscopic drainage system. (This liquid is not part of the tears on the outer surface of the eye.)

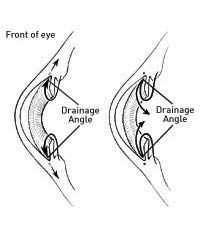

Because the eye is a closed structure, if the drainage area for the aqueous humor — called the drainage angle — is blocked, the excess fluid cannot flow out of the eye. Fluid pressure within the eye increases, pushing against the optic nerve and causing damage.

Clear liquid called aqueous humor is constantly being produced within the eye (left). If the drainage angle of the eye is blocked, fluid cannot flow out of the eye (right).

What are the different types of glaucoma?

Chronic open-angle glaucoma: This is the most common form of glaucoma in the United States.

The risk of developing chronic open-angle glaucoma increases with age. The drainage angle of the eye becomes less efficient over time, and pressure within the eye gradually increases, which can damage the optic nerve. In some patients, the optic nerve becomes sensitive even to normal eye pressure and is at risk for damage. Treatment is necessary to prevent further vision loss.

Typically, open-angle glaucoma has no symptoms in its early stages and vision remains normal. As the optic nerve becomes more damaged, blank spots begin to appear in the field of vision. You typically won't notice these blank spots in your day-to-day activities until the optic nerve is significantly damaged and these spots become large. If all the optic nerve fibers die, blindness results.

Closed-angle glaucoma: Some eyes are formed with the iris (the colored part of the eye) too close to the drainage angle. In these eyes, which are often small and farsighted, the iris can be sucked into the drainage angle and block it completely. Since the fluid cannot exit the eye, pressure inside the eye builds rapidly and causes an acute closed-angle attack.

Symptoms may include:

- blurred vision;

- severe eye pain;

- headache;

- rainbow-colored halos around lightsl

- nausea and vomiting

This is a true eye emergency. If you have any of these symptoms, call your ophthalmologist immediately. Unless this type of glaucoma is treated quickly, blindness can result.

Unfortunately, two-thirds of those with closed-angle glaucoma develop it slowly without any symptoms prior to an attack.

Who is at risk for glaucoma?

Your ophthalmologist considers many kinds of information to determine your risk for developing the disease.

The most important risk factors include:

- age;

- elevated eye pressure;

- family history of glaucoma;

- African or Spanish-American ancestry;

- farsightedness or nearsightedness;

- past eye injuries;

- thinner central corneal thickness;

- systemic health problems, including diabetes, migraine headaches, and poor circulation.

Your ophthalmologist will weigh all of these factors before deciding whether you need treatment for glaucoma, or whether you should be monitored closely as a glaucoma suspect. This means your risk of developing glaucoma is higher than normal, and you need to have regular examinations to detect the early signs of damage to the optic nerve.

How is glaucoma detected?

Regular eye examinations by your ophthalmologist are the best way to detect glaucoma. A glaucoma screening that checks only the pressure of the eye is not sufficient to determine if you have glaucoma. The only sure way to detect glaucoma is to have a complete eye examination.

During your glaucoma evaluation, your ophthalmologist will:

- measure your intraocular pressure (tonometry);

- inspect the drainage angle of your eye (gonioscopy);

- evaluate whether or not there is any optic nerve damage (ophthalmoscopy);

- test the peripheral vision of each eye (visual field testing, or perimetry).

Photography of the optic nerve or other computerized imaging may be recommended. Some of these tests may not be necessary for everyone. These tests may need to be repeated on a regular basis to monitor any changes in your condition.

How is glaucoma treated?

As a rule, damage caused by glaucoma cannot be reversed. Eyedrops, laser surgery and surgery in the operating room are used to help prevent further damage. In some cases, oral medications also may be prescribed. With any type of glaucoma, periodic examinations are very important to prevent vision loss. Because glaucoma can progress without your knowledge, adjustments to your treatment may be necessary from time to time.

Medications

Glaucoma is usually controlled with eyedrops taken daily. These medications lower eye pressure, either by decreasing the amount of aqueous fluid produced within the eye or by improving the flow through the drainage angle.

Never change or stop taking your medications without consulting your ophthalmologist. If you are about to run out of your medication, ask your ophthalmologist if you should have your prescription refilled. Glaucoma medications can preserve your vision, but they also may produce side effects. You should notify your ophthalmologist if you think you may be experiencing side effects.

Some eyedrops may cause:

- a stinging or itching sensation;

- red eyes or redness of the skin surrounding the eyes;

- changes in pulse and heartbeat;

- changes in energy level;

- changes in breathing (especially with asthma or emphysema);

- dry mouth;

- changes in sense of taste;

- headaches;

- blurred vision;

- change in eye color.

All medications can have side effects or can interact with other medications. Therefore, it is important that you make a list of the medications you regularly take and share this list with each doctor you see.

Laser Surgery

Laser surgery treatments may be recommended for different types of glaucoma.

In open-angle glaucoma, the drain itself is treated. The laser is used to modify the drain (trabeculoplasty) to help control eye pressure.

In closed-angle glaucoma, the laser creates a hole in the iris (iridotomy) to improve the flow of aqueous fluid to the drain.

Surgery in the Operating Room

When surgery in the operating room is needed to treat glaucoma, your ophthalmologist uses fine, microsurgical instruments to create a new drainage channel for the aqueous fluid to leave the eye. Surgery is recommended if your ophthalmologist feels it is necessary to prevent further damage to the optic nerve. As with laser surgery, surgery in the operating room is typically an outpatient procedure.

What is your part in treatment?

Treatment for glaucoma requires teamwork between you and your doctor. Your ophthalmologist can prescribe treatment for glaucoma, but only you can make sure that you follow your doctor's instructions and take your eyedrops. Once you are taking medications for glaucoma, your ophthalmologist will want to see you more frequently. Typically, you can expect to visit your ophthalmologist every three to four months. This will vary depending on your treatment needs.

Loss of vision can be prevented

Regular medical eye exams may help prevent unnecessary vision loss. Recommended intervals for eye exams are:

- Age 20-29: Individuals of African descent or with a family history of glaucoma should have an eye examination every three to five years. Others should have an eye exam at least once during this period.

- Age 30 -39: Individuals of African descent or with a family history of glaucoma should have an eye examination every two to four years. Others should have an eye exam at least twice during this period.

- Age 40-64: Every two to four years.

- Age 65 or older: Every one to two years.

© Copyright 2003 American Academy of Ophthalmology ®

[Back to top of page]

[Back to top of page]

Refractive Errors and Refractive Surgery

Introduction

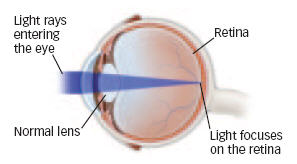

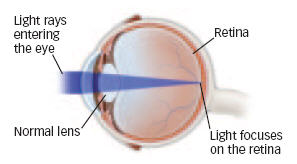

Vision occurs when light rays are bent or refracted by the cornea and lens and received by the retina, the nerve layer at the back of the eye, in the form of an image, which is sent through the optic nerve to the brain. Refractive errors occur when the shape of the eye doesn't refract light properly. The main types of refractive error are myopia (nearsightedness), hyperopia (farsightedness) and astigmatism (distortion). Presbyopia (aging eye) is a problem of the lens and is characterized by the inability to bring close objects into focus.

Refractive errors can be corrected with glasses, contact lenses or refractive surgery.

Why Is It In The News?

A growing consumer demand for correction of refractive errors, and ongoing clinical findings about refractive surgery innovations, outcomes and complications continue to receive widespread interest in the media.

Facts & Statistics

- Approximately 148 million people (52% of the population) in the United States wear some form of corrective eyewear.1

- Approximately 34 million people in the United States wear contact lenses.2

- Approximately 1.8 million refractive surgery procedures will be performed in 2002.3

- Approximately 63 million people in the United States are candidates for refractive surgery.3

- Laser in-situ keratomileusis (LASIK) accounts for approximately 95 percent of all refractive surgeries.3

- Photorefractive keratectomy (PRK) accounts for approximately five percent of refractive surgeries.3

- Other types of refractive surgery are: Intrastromal corneal ring segments (ICRS), plastic corneal inlays designed to correct low myopia and marketed under the name "Intacs;" Laser Thermal Keratoplasty (LTK), a nonincisional infrared laser treatment for correction of mild-to-moderate farsightedness; radial keratotomy (RK), a rarely used microsurgical procedure in which incisions are made in the cornea to reduce mild-to-moderate myopia; laser epithelium keratoplasty (LASEK), a variation of PRK in which the corneal surface (epithelium) is loosened and pushed to one side prior to use of the excimer laser to reshape the cornea; conductive keratoplasty (CK), the use of radio frequency waves to shrink corneal collagen for correction of low-to-moderate hyperopia; intraocular contact lens (ICL), an intraocular lens surgically inserted into the front section of the eye and placed over the eye's natural lens for correction of myopia, hyperopia, and astigmatism (currently in FDA clinical trials); scleral expansion band (SEB), crescent-shaped plastic or metal segments implanted into the white of the eye to reverse presbyopia (in investigational trials in Canada, Mexico, and France); laser presbyopia reversal (LPR), an infrared laser-based treatment, in clinical trials in Europe, United States, and Japan.4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12

- The excimer laser, a device that generates cool, ultraviolet light, was first used in clinical trials for PRK in 1987 and was approved by the FDA in 1994 for use in phototherapeutic keratectomy (PTK) and in 1995 for PRK.13

- The excimer laser was first used for LASIK in 1991 and was first approved for LASIK in 1998.13

Conclusions

Refractive surgery is intended for people who want to minimize reliance on glasses and contact lenses. It is important for patients to have realistic expectations. People looking for perfect vision without glasses or contacts run the risk of being disappointed.

However, continuing refinement and improvement of refractive surgery procedures mean that Eye M.D.s can offer more vision correction options to more people than ever before.

See additional sections on: Complications and Informed Consent; Finding and Assessing a Surgeon and Surgeon Training; Assessment of Candidates for Refractive Surgery and Glasses after Refractive Surgery; Refractive Surgery Advertising, Marketing, and Pricing.

References

- National Center for Health Statistics; Poe GS. Eye care visits and use of eyeglasses or contact lenses, United States, 1979 and 1980. Vital Health Statistics, 1984; 10:145.

- Contact Lens Council. Statistics/Web site, July 2001. Based on 1999 data.

- Spectrum Consulting; Arons I. 2001.

- Keravision, Inc. Physician Booklet: Intacs Corneal Ring Segments, 1999.

- Contact Lens Association of Ophthalmologists (CLAO); Brown DC. Laser Thermokeratoplasty: A New Tool for Refractive Surgeons and Comprehensive Ophthalmologists, Refractive Eyecare for Ophthalmologists, April 1999.

- American Academy of Ophthalmology. Radial Keratotomy for Myopia, Ophthalmic Technology Assessments, November 1992.

- American Academy of Ophthalmology Web Site; Stone A. ASCRS 2001 Highlights, May 2001.

- American Academy of Ophthalmology Web Site; Stone A. ASCRS 2001 More Highlights, May 2001.

- DuBosar R. Surgeons say phakic IOLs give better visual acuity than LASIK, Ocular Surgery News, July 1999.

- Cimberle M. ICL implantation shows 'excellent' results, Ocular Surgery News, July 1999.

- Chartres L. Surgical options for presbyopia have potential, Ocular Surgery News, February 2000.

- Guttman, C. Infrared laser presbyopia reversal trials to be expanded, Ophthalmology Times, October 1, 2000.

- FDA. Refractive Laser PMA Approvals, March 2001.

Copyright © American Academy of Ophthalmology®

[Back to top of page]

[Back to top of page]

Cataract Surgery

What is a cataract?

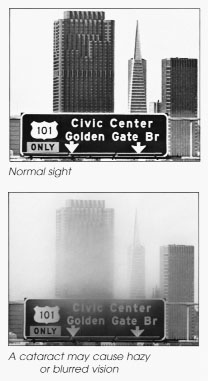

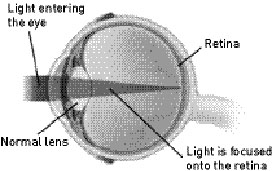

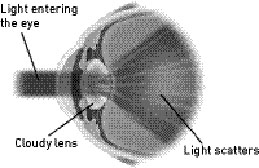

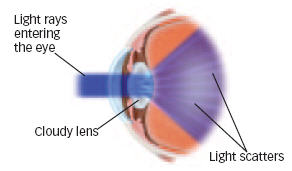

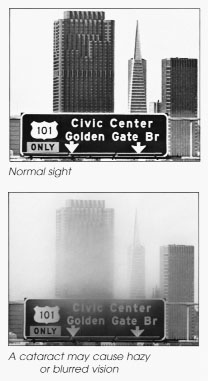

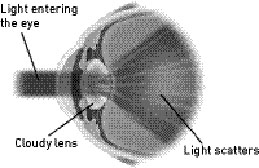

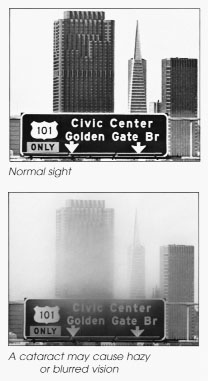

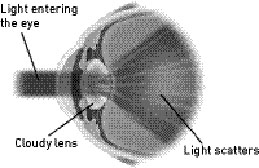

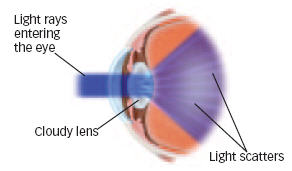

A cataract is a clouding of the eye's naturally clear lens. The lens focuses light rays on the retina — the layer of light-sensing cells lining the back of the eye — to produce a sharp image of what we see. When the lens becomes cloudy, light rays cannot pass through it easily, and vision is blurred.

Light rays entering an eye with a normal lens.

Light rays entering an eye with a cataract. When a cataract forms, the lens of your eye is cloudy.light cannot pass through it easily, and your vision

What causes cataracts?

Cataract development is a normal process of aging, but cataracts also develop from eye injuries, certain diseases or medications. Your genes may also play a role in cataract development.

How can a cataract be treated?

A cataract may not need to be treated if your vision is only slightly blurry. Simply changing your eyeglass prescription may help to improve your vision for a while. There are no medications, eyedrops, exercises or glasses that will cause cataracts to disappear once they have formed. Surgery is the only way to remove a cataract. When you are no longer able to see well enough to do the things you like to do, cataract surgery should be considered.

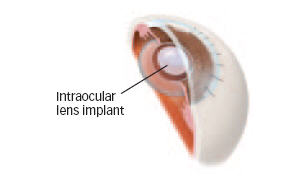

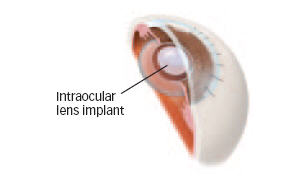

In cataract surgery, the cloudy lens is removed from the eye through a surgical incision. In most cases, the natural lens is replaced with a permanent intraocular lens (IOL) implant.

What can I expect if I decide to have cataract surgery?

Before Surgery

To determine if your cataract should be removed, your ophthalmologist (Eye M.D.) will perform a thorough eye examination. Before surgery, your eye will be measured to determine the proper power of the intraocular lens that will be placed in your eye. Ask your ophthalmologist if you should continue taking your usual medications before surgery.

You should make arrangements to have someone drive you home after surgery.

The Day of Surgery

Surgery is usually done on an outpatient basis, either in a hospital, an outpatient surgical center, or an ambulatory surgery center. You may be asked to skip breakfast, depending on the time of your surgery.

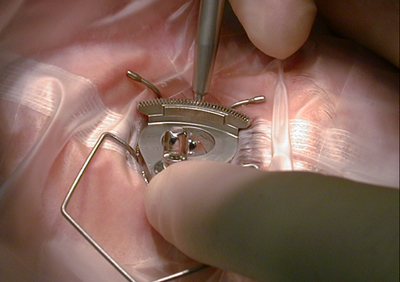

When you arrive for surgery, you will be given eyedrops and perhaps a mild sedative to help you relax. A local anesthetic will numb your eye. The skin around your eye will be thoroughly cleansed, and sterile coverings will be placed around your head. Your eye will be kept open by an eyelid speculum. You may see light and movement, but you will not be able to see the surgery while it is happening.

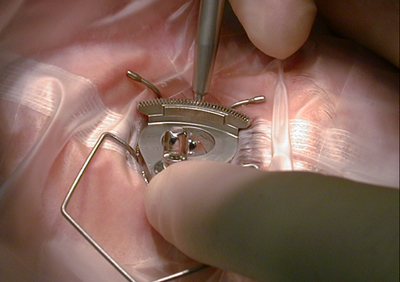

Under an operating microscope, a small incision is made in the eye. In most cataract surgeries, tiny surgical instruments are used to break apart and remove the cloudy lens from the eye. The back membrane of the lens (called the posterior capsule) is left in place.

During cataract surgery, tiny instruments are used to break apart and remove the cloudy lens from the eye.

An intraocular lens (iol) implant.

In cataract surgery, the intraocular lens replaces the eye's natural lens.

After surgery is completed, your doctor may place a shield over your eye. After a short stay in the outpatient recovery area, you will be ready to go home.

Following Surgery

You will need to:

- Use the eyedrops as prescribed

- Be careful not to rub or press on your eye

- Avoid strenuous activities until your ophthalmologist tells you to resume them

- Ask your doctor when you can begin driving

- Wear eyeglasses or an eye shield, as advised by your doctor

You can continue most normal daily activities. Over-the-counter pain medicine may be used, if necessary.

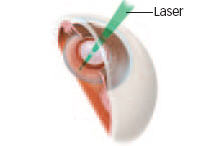

Is a laser used during cataract surgery?

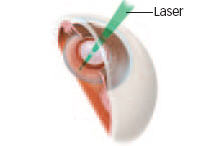

Laser surgery is not used in cataract removal surgery. However, the lens capsule (the part of the eye that holds the lens in place) sometimes becomes cloudy several months or years after the original cataract operation. If the cloudy capsule blurs your vision, your ophthalmologist can perform a second surgery using a laser. During the second procedure, called a posterior capsulotomy, a laser is used to make an opening in the cloudy lens capsule, restoring normal vision.

Posterior capsulotomy: a laser is used to make an opening in the cloudy lens capsule.

Will cataract surgery improve my vision?

The success rate of cataract surgery is excellent. Improved vision is achieved in the majority of patients. Only a small number of patients continue to have problems following cataract surgery.

Complications After Cataract Surgery

Though they rarely occur, serious complications of cataract surgery are:

- Infection

- Bleeding

- Swelling

- Detachment of the retina

Call your ophthalmologist immediately if you have any of the following symptoms after surgery:

- Pain not relieved by nonprescription pain medication

- Loss of vision

- Nausea, vomiting, or excessive coughing

- Injury to the eye

Even if cataract surgery is successful, some patients may not see as well as they would like to. Other eye problems such as macular degeneration (aging of the retina), glaucoma or diabetic retinopathy may limit vision after surgery. Even with these problems, cataract surgery may still be worthwhile.

Copyright © July 2004 American Academy of Ophthalmology®

[Back to top of page]

[Back to top of page]

Cataract Surgery in the Second Eye

This article was written for physicians. Patients should talk to their Eye M.D. if they have questions about the content.

Indications for Surgery

The primary indication for surgery is when vision impaired by cataract no longer meets the patient's needs and surgery provides a reasonable likelihood of improved visual function. Cataract removal is also indicated when there is evidence of lens-induced disease (e.g., phakomorphic glaucoma, phakolytic glaucoma, etc.) or when it is necessary to visualize the fundus in an eye that has the potential for sight (the latter includes a diabetic patient who is at risk of visual loss from retinopathy or other special investigations that demonstrate intraocular pathology, both of which require clear media for optimal management).

Benefits of Second-Eye Surgery

Cataract surgery in both eyes is an appropriate treatment for patients with bilateral cataract-induced visual impairment in order to restore binocular vision. Three studies comparing the outcomes of first- and second-eye surgeries after extracapsular cataract extraction concluded that patients who underwent surgery in both eyes had greater improvement in functional status than did those who underwent surgery in one eye,1-3 and another study demonstrated improved binocular function and ability to meet a driving standard.4 Patients who had surgery in both eyes also have been shown to have statistically significant improvement in satisfaction with vision than patients who had surgery in only one eye.2 Another study demonstrated that the cataractous eye interfered with the function of the pseudophakic eye, and after surgery on the second eye, multiple complaints of visual disability were eliminated.5

Timing

Consideration of the appropriate interval between the first-eye surgery and second-eye surgery is influenced by several factors: the patient's visual needs, the patient's preferences, visual acuity or function in the second eye, the medical and refractive stability of the first eye, the need to develop binocular vision and the presence of symptomatic anisometropia as well as logistical concerns of the patient in traveling back and forth to the physician's office. The patient and ophthalmologist should discuss the benefit, risk and timing of second-eye surgery when they have had the opportunity to evaluate the results of surgery on the first eye.

Conclusion

Patients receiving second-eye surgery experience significant improvement in visual function. The indication for second-eye surgery is the same as for the first eye. Prior to performing surgery on the second eye, the patient's first eye should have a stable postoperative refraction and the patient should perceive improved function, and sufficient time should have elapsed to evaluate and treat early postoperative complications, such as endophthalmitis. In addition, the patient needs sufficient time to assess the results of his or her first-eye surgery to determine the need and appropriate timing for surgery in the second eye.

References

- Javitt JC, Brenner MH, Curbow B, et al: Outcomes of cataract surgery-improvement in visual acuity and subjective visual function after surgery in the first, second, and both eyes. Arch Ophthalmol 1993; 111:686-91.

- Javitt JC, Steinberg EP, Sharkey P, et al: Cataract surgery in one eye or both: a billion dollar per year issue. Ophthalmology 1995; 102:1583-93.

- Cassells X, Alonso J, Ribo C, et al: Comparison of the results of first and second cataract eye surgery. Ophthalmology 1999; 106:676-82.

- Talbot EM, Perkins A: The benefit of second eye cataract surgery. Eye 1998; 983-9.

- Laidlaw A, Harrad R: Can second eye cataract extraction be justified? Eye 1993; 7:680-6.

© Copyright 2000 American Academy of Ophthalmology

[Back to top of page]

[Back to top of page]

Lasik

What is LASIK? Laser assisted in situ keratomileusis, or LASIK, is an outpatient surgical procedure used to treat myopia (nearsightedness), hyperopia (farsightedness), and astigmatism. With LASIK, your ophthalmologist (Eye M.D.) uses a microsurgical instrument and a laser to reshape the cornea (the clear covering of the eye) to improve the way the eye focuses light rays onto the retina. LASIK may decrease your dependence on glasses and contacts or, in some cases, allow you to do without them entirely. According to the American Academy of Ophthalmology, seven out of 10 LASIK patients achieve 20/20 vision, but 20/20 does not always mean perfect vision. If you have LASIK to correct your distance vision, you'll probably still need reading glasses by around age 45. Therefore, it is important for you to consider the possibility that LASIK may not give you perfect vision.

Am I a good candidate for LASIK? LASIK is not for everyone, and your ophthalmologist will advise you about certain conditions that may prevent you from being a good candidate for this procedure. For instance, the ideal candidate for LASIK is over 18 years of age, not pregnant or nursing, and free of any eye disease. You should not have had a change in your eye prescription in the last year and should have a refractive error within the range of correction for LASIK. You also must be willing to accept the potential risks, complications and side effects associated with LASIK (listed in this article). You should discuss these issues with your surgeon, carefully weighing the risks and rewards. If you're happy wearing contacts or glasses, you may want to forego the surgery.

What happens before surgery? Your ophthalmologist will perform a thorough eye exam to measure your prescription and check for any abnormalities that might affect the procedure. Your doctor will check your eyes for unusual dryness, which could cause dry eye symptoms post-operatively, or unusually large pupils, which could affect night or low-light vision.

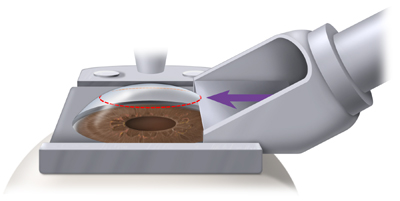

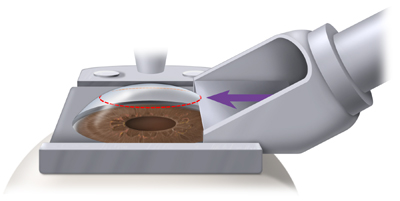

How is LASIK done? LASIK is performed in a reclining chair in an outpatient surgical suite. First, the eye is numbed with a few drops of topical anesthetic. These drops may sting. An eyelid holder (called a speculum) is placed between the eyelids to keep them open and prevent you from blinking. A suction ring placed on the eye lifts and flattens the cornea and helps keep your eye from moving. You may feel pressure from the eyelid holder and suction ring, similar to a finger pressed firmly on your eyelid. From the time the suction ring is put on the eye until it is removed, vision appears dim or goes black.

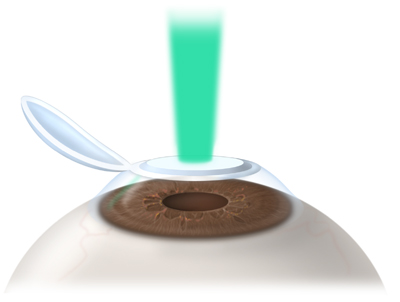

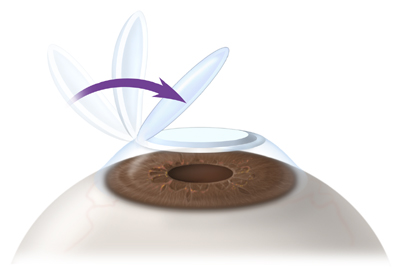

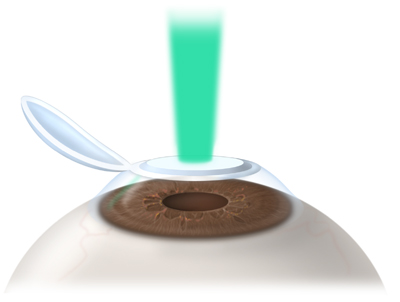

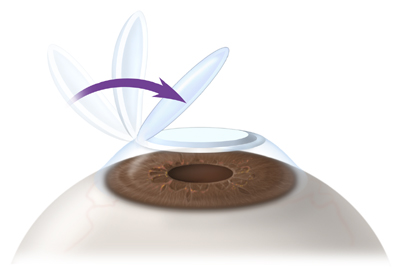

An automated microsurgical instrument called a microkeratome is attached to the suction ring. As the microkeratome blade moves across the cornea, you will hear a buzzing sound. The microkeratome stops at a preset point, far enough from the edge of the cornea to create a hinged flap of paper-thin corneal tissue. The microkeratome and the suction ring are removed from your eye, and the flap is lifted and folded back. As the flap moves, your vision gets blurrier. The laser, preprogrammed with measurements customized to your eye, is then centered above the eye. In most cases, a pupil tracker will be used to keep the laser centered on your pupil during surgery. You will stare at a special pinpoint light called a fixation light or target light while the laser sculpts the exposed corneal tissue. The laser makes a clicking sound that can be heard during the procedure. After the laser has completed reshaping the cornea, the surgeon places the flap back into position and smoothes the edges. The flap adheres on its own in two to three minutes.

The microkeratome blade lifts the corneal tissue.

The microkeratome blade lifts the corneal tissue.  The laser sculpts the exposed surface of cornea.

The laser sculpts the exposed surface of cornea.  The tissue flap is replaced. What happens after surgery?

The tissue flap is replaced. What happens after surgery? To help protect cornea as it heals, your ophthalmologist may place a see-through shield over your eye, if needed, or may ask you to wear a shield at night. It is normal for your eye to burn or feel scratchy. This usually disappears in a few hours. Plan on going home and taking a nap or just relaxing after the procedure. You will be given eyedrops to help the eye's healing and to alleviate dryness. Healing after LASIK is usually less uncomfortable than with other methods of refractive surgery because the laser removes tissue from the inside of the cornea and not from the more sensitive corneal surface.

Risks, Complications and Side Effects LASIK, like any surgery, has risks and complications that should be carefully considered. LASIK can sometimes result in undercorrection or overcorrection. Fortunately, these problems can often be improved with glasses, contact lenses, or an additional laser surgery. Most complications can be treated without any loss of vision. Permanent vision loss is very rare. There is a chance, though extremely small, that your vision will not be as good after the surgery as before, even with glasses or contacts. This is called a loss of best corrected vision. Some people experience temporary side effects after LASIK that usually disappear over time. In rare situations, they may be permanent. These side effects may include:

- Discomfort or pain

- Hazy or blurry vision

- Scratchiness

- Dryness

- Glare

- Haloes or starbursts around lights

- Light sensitivity

- Small pink or red patches on the white of the eye

Almost everyone experiences some dryness in the eyes and fluctuating vision during the day. These symptoms usually fade within one month, although some people may continue to have symptoms for a longer period of time. Infection is a small possibility with any surgical procedure, including LASIK. Antibiotics can usually clear such infections. Rarely, complications during surgery may cause irregularities in the corneal flap, requiring further treatment.

What will my vision be like after LASIK? It is important that anyone considering LASIK have realistic expectations. LASIK allows people to perform most of their everyday tasks without corrective lenses. However, people looking for perfect vision without glasses or contacts run the risk of being disappointed. Over 90 percent of people who have LASIK achieve somewhere between 20/20 and 20/40 vision without glasses or contact lenses. If vision is undercorrected after the procedure, your doctor may decide to perform a second surgery, called an enhancement, to further refine the result. LASIK cannot correct presbyopia, the age-related loss of close-up focusing power. With or without refractive surgery, almost everyone who has excellent distance vision will need reading glasses by the time they reach 40 or 50 years old. Some people choose a vision correction method called monovision, which leaves one eye slightly nearsighted. The nearsighted eye is used for close work, while the other eye is adjusted for distance vision. Although monovision is acceptable for most people, some may not be comfortable with this correction. To determine your individual needs and your ability to adapt to this correction, you may wish to try monovision with contact lenses before surgery. If 20/20 vision is essential for your career or leisure activities, consider whether 20/40 vision would be good enough for you. You should be comfortable with the possibility that you may need a second surgery, or that you might need to wear glasses for certain things, such as reading or driving at night.

Summary Today's LASIK procedure is the most popular form of refractive surgery for decreasing dependence on eyeglasses or contact lenses. If LASIK surgery is appropriate for your eyes, you could join thousands of people who have benefited from this widely performed procedure. To make the decision that's right for you, discuss with your ophthalmologist whether or not you are a good candidate for LASIK.

Copyright © September 2005 American Academy of Ophthalmology®

[Back to top of page]

[Back to top of page]

Appropriate Management of the Refractive Surgery Patient

Background

The term refractive surgery describes various procedures that modify the refractive error of the eye. Most of these procedures involve altering the cornea and are collectively referred to as keratorefractive surgery, refractive keratoplasty, or refractive corneal surgery. Refractive surgery may be considered when a patient wishes to be less dependent on spectacles or contact lenses, or when there are occupational or cosmetic reasons not to wear spectacles. Refractive surgery is an elective procedure. The surgeon must provide thorough informed consent of its risks, benefits, alternatives and limitations. The outcome of refractive surgery is not totally predictable; glasses or contact lenses may be necessary to obtain satisfactory distance vision after surgery, and postsurgical patients who are presbyopic will likely require reading glasses.

The Informed Patient

The decision to undergo refractive surgery should follow an appropriate period of information gathering by patients. They may learn about the procedures through the lay and scientific press, marketing materials (including print, radio and television advertisements), Internet Web sites, informational brochures, video tapes, discussions with ophthalmologists, medical doctors other than ophthalmologists, and other eye care professionals. It is the obligation of all health care professionals who provide information about refractive surgery to assure that the information is accurate, unbiased, and balanced, including a description of the potential risks and benefits of and alternatives to refractive surgery. The patient also has the right to know in advance of surgery who is expected to be participating in, and who will be responsible for, perioperative care and the professional training, experience, and qualifications of persons expected to be participating in that care, and the patient is free to give or withhold consent to these arrangements. The ultimate responsibility for obtaining accurate preoperative assessment and the patient's informed consent to refractive surgery rests with the ophthalmologist who performs the surgery.

Performance of Surgery

Surgical treatment of refractive error, including excimer laser surgery, is appropriately performed by ophthalmologists who have advanced specialized training and experience in refractive surgery. An ophthalmologist's advanced specialized training in refractive surgery will generally include appropriate didactic courses, personal observation (on site or via unedited video) of live surgery performed by experienced refractive surgeons, wet laboratory hands-on experiences under the supervision of an experienced refractive surgeon, optional confirmation of knowledge and skills transfer through written examinations, monitoring by an experienced refractive surgeon of the ophthalmologist's first 10 to 20 refractive surgery cases, and attendance at annual continuing medical education courses for maintenance of the ophthalmologist's refractive surgical skills.

Perioperative Care

The ophthalmologist who performs the surgery is responsible for the care of the patient during the postoperative period, during which time additional medical treatment (e.g., antibiotics, corticosteroids, other anti-inflammatory drugs and analgesics) and/or surgical therapy might be indicated to minimize discomfort and maximize the likelihood of a positive outcome for the patient. The length of time involved in the important postoperative period of healing and modification of therapy varies substantially among different surgical procedures and patient healing responses. Although the risk is low, serious vision-threatening complications, such as infections, may occur after both incisional and laser refractive surgery. The ophthalmologist who performs the refractive surgery is ultimately responsible for the preoperative evaluation, the surgical procedure itself, and postoperative care of patients undergoing refractive surgery.

Appropriate Role of Other Providers After Surgery

After refractive surgery, regular follow up of patients at the appropriate time in the postoperative period by nonphysician eye care providers may be acceptable practice in selected instances, with the advance consent of the patient. A substantial percentage of patients may require, or desire, full- or part-time use of corrective lenses, including spectacles and contact lenses. The optical management of patients including monitoring and measuring changes in refractive error and corneal topography, may be performed either by the ophthalmologist who performed the surgery, by other ophthalmologists, by other physicians, or by nonphysicians who are professionally trained, experienced and qualified to do so at the appropriate time in the postoperative period.

The ophthalmologist who performs refractive surgery on a patient retains the ultimate responsibility for the perioperative care of the patient, even if the surgeon chooses to entrust any aspect of perioperative care to another physician or a health professional who is not a physician. However, it is considered appropriate for physicians other than the ophthalmologist who performed the refractive surgery or nonphysicians to participate in the perioperative care of refractive surgery patients in conformity to the following guidelines, provided the patient is promptly referred to the operating ophthalmic surgeon or other equivalently trained ophthalmologist for evaluation of the need for further medical and surgical treatment in the event of unsatisfactory healing or complication if:

- Prior to the surgery there is mutual agreement between the ophthalmologist who performed the refractive surgery and another physician or a nonphysician regarding their respective roles and responsibilities in the care of the patient.

- The ophthalmic surgeon delegates to the other physician or nonphysician the performance of only those services that are not within the unique competence of the ophthalmic surgeon and that the other physician or nonphysician is legally entitled and professionally trained, experienced and qualified to perform.

- In advance of surgery, the patient is accurately informed of the role that the other physician or nonphysician will play in the delivery of care and consents to these arrangements.

- The ophthalmologist who performs the surgery or an equivalently trained ophthalmologist is available to provide, when and as required, any medical, surgical, or other care that the other physician or the nonphysician is not legally entitled or professionally trained, experienced or qualified to perform.

Approved by the Secretary for Quality of Care and Knowledge Base Development: August 30, 2004

Copy © 2004 American Academy of Ophthalmology®

[Back to top of page]

[Back to top of page]

Cataract

What is a cataract?

A cataract is a clouding of the normally clear lens of the eye. It can be compared to a window that is frosted or yellowed.

There are many misconceptions about cataract. Cataract is not:

- a film over the eye;

- caused by overusing the eyes;

- spread from one eye to the other;

- a cause of irreversible blindness.

Common symptoms of cataract include:

- a painless blurring of vision;

- glare, or light sensitivity;

- poor night vision;

- double vision in one eye;

- needing brighter light to read;

- fading or yellowing of colors.

The amount and pattern of cloudiness within the lens can vary. If the cloudiness is not near the center of the lens, you may not be aware that a cataract is present.

What causes cataract?

The most common type of cataract is related to aging of the eye. Causes of cataract include:

- family history;

- medical problems, such as diabetes;

- injury to the eye;

- medications, especially steroids;

- long-term, unprotected exposure to sunlight;

- previous eye surgery;

- unknown factors.

How is a cataract detected?

A thorough eye examination by your ophthalmologist (Eye M.D.) can detect the presence of a cataract, as well as any other conditions that may be causing blurred vision or other eye problems.

Problems with other parts of the eye (eg, cornea, retina, optic nerve) can be responsible for vision loss and may prevent you from having much or any improvement in vision after cataract surgery. If improvement in your vision is unlikely, cataract removal may not be recommended. Your ophthalmologist can tell you how much visual improvement is likely.

How fast does a cataract develop?

How quickly the cataract develops varies among individuals, and may even be different between the two eyes. Most age-related cataracts progress gradually over a period of years.

Other cataracts, especially in younger people and people with diabetes, may progress rapidly over a short time. It is not possible to predict exactly how fast cataracts will develop in any given person.

How is cataract treated?

Surgery is the only way a cataract can be removed. However, if symptoms of cataract are not bothering you very much, surgery may not be needed. Sometimes a simple change in your eyeglass prescription may be helpful.

There are no medications, dietary supplements or exercises that have been shown to prevent or cure cataracts.

Protection from excessive sunlight may help slow the progression of cataracts. Sunglasses that screen out ultraviolet (UV) light rays or regular eyeglasses with a clear, anti-UV coating offer this protection.

When should surgery be done?

Surgery should be considered when cataracts cause enough loss of vision to interfere with your daily activities.

It is not true that cataracts need to be "ripe" before they can be removed, or that they need to be removed just because they are present.

Cataract surgery can be performed when your visual needs require it. You must decide if you can see to do your job and drive safely or, if you can read and watch TV in comfort. Can you see well enough to perform daily tasks, such as cooking, shopping, yard work or taking medications without difficulty?

Based on your symptoms, you and your ophthalmologist should decide together when surgery is appropriate.

What can I expect from cataract surgery?

Over 1.4 million people have cataract surgery each year in the United States, and more than 95% of those surgeries are performed with no complications.

During cataract surgery, which is usually performed under local or topical anesthesia as an outpatient procedure, the cloudy lens is removed from the eye. In most cases, the focusing power of the natural lens is restored by replacing it with a permanent intraocular lens implant.

Your ophthalmologist performs this delicate surgery using a microscope, miniature instruments and other modern technology.

In many people who have cataract surgery, the natural capsule that supports the intraocular lens becomes cloudy. Laser surgery is used to open this cloudy capsule, restoring clear vision.

You will have to take eyedrops as your ophthalmologist directs. Your surgeon will check your eye several times to make sure it is healing properly.

Cataract surgery is a highly successful procedure. Improved vision is the result in over 95% of cases, unless there is a problem with the cornea, retina, optic nerve or other structures. It is important to understand that complications can occur during or after the surgery, some severe enough to limit vision. If you experience even the slightest problem after cataract surgery, your ophthalmologist will want to hear from you immediately.

Conclusion

Cataracts are a common cause of decreased vision, particularly for the elderly, but they are treatable. Your ophthalmologist can tell you whether cataract or some other problem is the cause of your vision loss and can help you decide if cataract surgery is appropriate for you.

Cataract

What is a cataract?

A cataract is a clouding of the normally clear lens of the eye. It can be compared to a window that is frosted or yellowed.

There are many misconceptions about cataract. Cataract is not:

- a film over the eye;

- caused by overusing the eyes;

- spread from one eye to the other;

- a cause of irreversible blindness.

Common symptoms of cataract include:

- a painless blurring of vision;

- glare, or light sensitivity;

- poor night vision;

- double vision in one eye;

- needing brighter light to read;

- fading or yellowing of colors.

The amount and pattern of cloudiness within the lens can vary. If the cloudiness is not near the center of the lens, you may not be aware that a cataract is present.

What causes cataract?

The most common type of cataract is related to aging of the eye. Causes of cataract include:

- family history;

- medical problems, such as diabetes;

- injury to the eye;

- medications, especially steroids;

- long-term, unprotected exposure to sunlight;

- previous eye surgery;

- unknown factors.

How is a cataract detected?

A thorough eye examination by your ophthalmologist (Eye M.D.) can detect the presence of a cataract, as well as any other conditions that may be causing blurred vision or other eye problems.

Problems with other parts of the eye (eg, cornea, retina, optic nerve) can be responsible for vision loss and may prevent you from having much or any improvement in vision after cataract surgery. If improvement in your vision is unlikely, cataract removal may not be recommended. Your ophthalmologist can tell you how much visual improvement is likely.

How fast does a cataract develop?

How quickly the cataract develops varies among individuals, and may even be different between the two eyes. Most age-related cataracts progress gradually over a period of years.

Other cataracts, especially in younger people and people with diabetes, may progress rapidly over a short time. It is not possible to predict exactly how fast cataracts will develop in any given person.

How is cataract treated?

Surgery is the only way a cataract can be removed. However, if symptoms of cataract are not bothering you very much, surgery may not be needed. Sometimes a simple change in your eyeglass prescription may be helpful.

There are no medications, dietary supplements or exercises that have been shown to prevent or cure cataracts.

Protection from excessive sunlight may help slow the progression of cataracts. Sunglasses that screen out ultraviolet (UV) light rays or regular eyeglasses with a clear, anti-UV coating offer this protection.

When should surgery be done?

Surgery should be considered when cataracts cause enough loss of vision to interfere with your daily activities.

It is not true that cataracts need to be "ripe" before they can be removed, or that they need to be removed just because they are present.

Cataract surgery can be performed when your visual needs require it. You must decide if you can see to do your job and drive safely or, if you can read and watch TV in comfort. Can you see well enough to perform daily tasks, such as cooking, shopping, yard work or taking medications without difficulty?

Based on your symptoms, you and your ophthalmologist should decide together when surgery is appropriate.

What can I expect from cataract surgery?

Over 1.4 million people have cataract surgery each year in the United States, and more than 95% of those surgeries are performed with no complications.

During cataract surgery, which is usually performed under local or topical anesthesia as an outpatient procedure, the cloudy lens is removed from the eye. In most cases, the focusing power of the natural lens is restored by replacing it with a permanent intraocular lens implant.

Your ophthalmologist performs this delicate surgery using a microscope, miniature instruments and other modern technology.

In many people who have cataract surgery, the natural capsule that supports the intraocular lens becomes cloudy. Laser surgery is used to open this cloudy capsule, restoring clear vision.

You will have to take eyedrops as your ophthalmologist directs. Your surgeon will check your eye several times to make sure it is healing properly.

Cataract surgery is a highly successful procedure. Improved vision is the result in over 95% of cases, unless there is a problem with the cornea, retina, optic nerve or other structures. It is important to understand that complications can occur during or after the surgery, some severe enough to limit vision. If you experience even the slightest problem after cataract surgery, your ophthalmologist will want to hear from you immediately.

Conclusion

Cataracts are a common cause of decreased vision, particularly for the elderly, but they are treatable. Your ophthalmologist can tell you whether cataract or some other problem is the cause of your vision loss and can help you decide if cataract surgery is appropriate for you.

Copyright © 2003 American Academy of Ophthalmology®

[Back to top of page]

[Back to top of page]

What Is UV Radiation?

Ultraviolet (UV) is an invisible form of radiation from sunlight that causes damage to the eyes and skin.

UV radiation can also emit artificially from welding arcs and tanning beds.

What Is the Difference Between UV Rays?

Three types of UV rays exist, including UVA, UVB and UVC. However, only UVA and UVB rays cause damage to our skin and eyes. Fortunately, UVC is absorbed by the atmosphere and never reaches the ground.

The following describes the differences between UVA and UVB rays:

UVA Rays:

- Cause eye damage and are a suspect in the development of cataracts, macular degeneration and aging of the retina

- Promote wrinkling of the skin and premature aging

- Burn deeper into the skin than UVB rays and may lead to skin cancer

- Pass through glass A

- re weaker and longer-wave lengths than UVB rays

UVB Rays:

- Damage the cornea (surface of the eye), similar to a sunburn on the skin

- Are most intense at high altitudes and low latitudes

- Cause sunburns and skin cancer

- Can’t pass through glass

- Are stronger and shorter than UVA rays

What Factors Affect the Intensity of UV Radiation?

- Weather. Do not be fooled on a cloudy day. Be careful under haze and thin clouds. It may not be hot outdoors, but the sun's rays can still burn.

- Environment. You receive higher UV exposure on snow, sand, water, and concrete because these surfaces reflect UV rays.

- Altitude. You also get more UV radiation at high altitudes, such as the mountains, and low latitudes, such as areas close to the Equator or the Caribbean. UV rays become weaker at the earth's poles.

- Length of time outdoors. The more time you spend in the sun, the more ultraviolet light you receive.

- Attire. Summer clothes expose the skin to more UV rays. Not wearing appropriate sunglasses expose the eyes to more harmful rays.

- Time of Day. UV radiation is highest between 10:00 am and 4:00 pm. In other words, if your shadow is shorter than you, UV radiation is at a higher intensity. If your shadow is longer, UV radiation is at a lower intensity.

- Season. UV radiation is the least intense in the winter, highest in the spring and summer (May to August), and lower in the fall.

Who Is at Risk for Eye Damage Caused by Ultraviolet Light?

Everyone, even children, is at risk for vision loss caused by UV radiation. Any factor that increases your exposure to sunlight, such as prescription drugs that increase sensitivity to UV light, can increase your risk of eye disorders. People who work outdoors or engage in leisure activities outside, especially in the snow or near water, are at the highest risk. People who are fair-skinned and have light eye color are also more at risk.

Copyright © 2002 American Academy of Ophthalmology ® All rights reserved.

[Back to top of page]

[Back to top of page]

Routine Preoperative Laboratory Testing for Patients Scheduled for Cataract Surgery

This article was written for physicians. Patients should talk to their Eye M.D. if they have questions about the content.

Introduction

Cataract surgery is the most common operation performed in the Medicare population. It has been proven to be a highly effective and safe procedure, with significant improvement in visual function and quality of life. In the past, the traditional approach for patients scheduled for cataract surgery was a comprehensive medical evaluation, including laboratory testing. However, there has been uncertainty over the effectiveness of preoperative medical testing such as complete blood counts (CBC), serum electrolytes, and electrocardiograms (EKG), and variation found in patterns of medical testing across the country. A survey reported that a significant proportion of the physicians did not believe that the tests were clinically necessary, but ordered them anyway due to institutional requirements, medicolegal concerns, or because they believed that another specialist wanted them performed.1 The direct cost to Medicare for routine medical testing prior to cataract surgery is estimated at $150 million each year.2

Background

In 1994, the Agency for Health Policy and Research initiated the Study of Medical Testing for Cataract Surgery.3 The purpose was to assess whether routine medical testing prior to cataract surgery reduces the rate of complications in the perioperative interval.

A large randomized controlled trial involved nine clinical centers, including private practices utilizing free-standing ambulatory surgery centers, community hospitals and academic medical centers. The study enrolled 18,189 patients scheduled to undergo 19,557 cataract surgeries, with 9,408 patients not receiving routine medical testing and 9,411 patients receiving routine testing. Follow-up data were 100% complete for the day of surgery and 99.8% complete for one week after surgery. The two groups of patients studied were comparable in age, sex, race, coexisting illnesses, American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) risk class and self-reported health status. This study excluded patients who were to receive general anesthesia, who had a myocardial infarction within the preceding three months, and who could not speak English or Spanish.

This study demonstrated that routine preoperative laboratory testing in patients scheduled to undergo cataract surgery is not necessary. A preoperative history and physical examination was performed, and patients were randomized to routine testing (CBC, EKG, electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine and glucose) versus testing only if a finding on the history or physical would have lead to a lab test even without the planned cataract surgery. Patients in both groups did have a finger-stick blood sugar if they were diabetic.

The overall rate of medical complications following cataract surgery was low, and generally were not serious or life-threatening. Adverse events developed at the time of surgery or within seven days of surgery in about 3% of cases in each group. Patients who had undergone routine medical testing did not have fewer adverse events, even when stratifying patients by age, sex, race, physical status and medical history.

This large, randomized controlled and multi-center trial provides strong evidence that routine use of laboratory tests prior to cataract surgery is not necessary and does not lead to improved outcomes. Perioperative morbidity and mortality were not decreased by the use of routine medical testing. Financial resources saved by elimination of unnecessary routine tests could be used for other patient care needs.

Conclusion

Routine medical tests performed on patients before cataract surgery are unnecessary because they do not increase the safety of the procedure. Preoperative medical tests can be ordered when a finding on a history or physical examination indicates a need, even if surgery were not scheduled.

References

- Bass EB, Steinberg EP, Luthra et al: Do ophthalmologists, anesthesiologists, and internists agree about preoperative testing in health patients undergoing cataract surgery? Arch Ophthalmol 1995; 113:1248-56.

- Schein OD: Assessing what we do: the example of preoperative medical testing. Arch Ophthalmol 1996; 114:1129-31.

- Schein OD, Katz J, Bass, EB et al: The value of routine preoperative medical testing before cataract surgery. NEJM 2000; 342:168-75

© Copyright 2000 American Academy of Pediatrics

[Back to top of page]

[Back to top of page]

An automated microsurgical instrument called a microkeratome is attached to the suction ring. As the microkeratome blade moves across the cornea, you will hear a buzzing sound. The microkeratome stops at a preset point, far enough from the edge of the cornea to create a hinged flap of paper-thin corneal tissue. The microkeratome and the suction ring are removed from your eye, and the flap is lifted and folded back. As the flap moves, your vision gets blurrier. The laser, preprogrammed with measurements customized to your eye, is then centered above the eye. In most cases, a pupil tracker will be used to keep the laser centered on your pupil during surgery. You will stare at a special pinpoint light called a fixation light or target light while the laser sculpts the exposed corneal tissue. The laser makes a clicking sound that can be heard during the procedure. After the laser has completed reshaping the cornea, the surgeon places the flap back into position and smoothes the edges. The flap adheres on its own in two to three minutes.

An automated microsurgical instrument called a microkeratome is attached to the suction ring. As the microkeratome blade moves across the cornea, you will hear a buzzing sound. The microkeratome stops at a preset point, far enough from the edge of the cornea to create a hinged flap of paper-thin corneal tissue. The microkeratome and the suction ring are removed from your eye, and the flap is lifted and folded back. As the flap moves, your vision gets blurrier. The laser, preprogrammed with measurements customized to your eye, is then centered above the eye. In most cases, a pupil tracker will be used to keep the laser centered on your pupil during surgery. You will stare at a special pinpoint light called a fixation light or target light while the laser sculpts the exposed corneal tissue. The laser makes a clicking sound that can be heard during the procedure. After the laser has completed reshaping the cornea, the surgeon places the flap back into position and smoothes the edges. The flap adheres on its own in two to three minutes.